Interview: B Michael Frolic

We interview the author of the excellent new "Canada and China: A 50 Year Journey"

B Michael Frolic is now in his 80s, and spent 62 of his years on earth between China and Canada. A former diplomat turned author, academic and storyteller, Mr. Frolic is one of a handful of Canadians alive today who can say they were there from the very beginning of Sino-Canadian relations right through to the Meng-2-Michaels era.

As a guest, he’s genuine, funny, curious and razor-sharp. We spoke for well over an hour and the following is a lightly edited transcript of the conversation.

Maple Kingdom: Your newest book, “Canada and China: A Fifty-Year Journey,” is from U of T Press and it charts a path from Pierre Trudeau recognizing China in 1970 through to The 2 Michaels era. I’d love for us to begin by discussing a little bit the different eras of the Canada-China relationship as you describe them in the book.

B. Michael Frolic: I first went to China in 1965. I’m a pretty old guy by now, but in 1965, I was a graduate student finishing a PhD on Soviet local government. I had spent the year in Moscow. and was doing field research in Siberia close to the border with China.

China and Russia at that point had fallen apart. They were no longer comrades together. There was a split, and likely a war--which happened later in ’69. In ’65, I said, “Great, I will be in Siberia, will try to get a visa to go to China, spend a month there, and see what’s going on. Maybe the Chinese version of communism is better than that of Russia.”

The Chinese students at the university in Moscow were constantly arguing with the Russians over the future of Marxism, and how to implement it. I said, “Yeah, I should really find out what they’re up to, and I’m going to be that close, right? It’s an opportunity.” Almost no Canadians had been to China.

We didn’t even recognize China. So that’s the first part of my story: that I went to China in ’65. I saw a very poor country, wary of foreigners, ready to start a Cultural Revolution and become tremendously politicized.

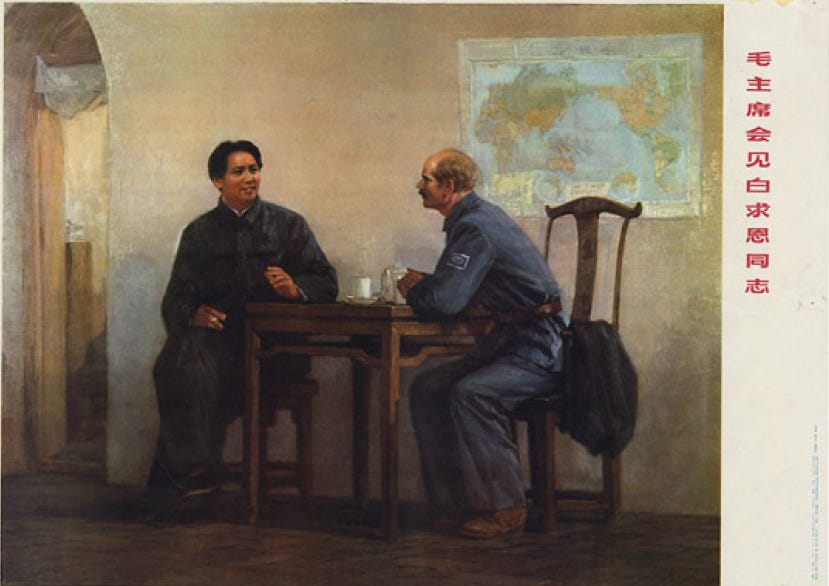

The contrast between then and now – the skyscrapers and the bullet trains--the tremendous changes – they are so staggering. But if you go back 50 years ago, China was really poor. Also, we knew nothing about China, and they knew nothing about us. The only Canadian that they knew anything about was Norman Bethune, because Chairman Mao had written an essay about how heroic he was – even though he was a foreigner, he helped China.

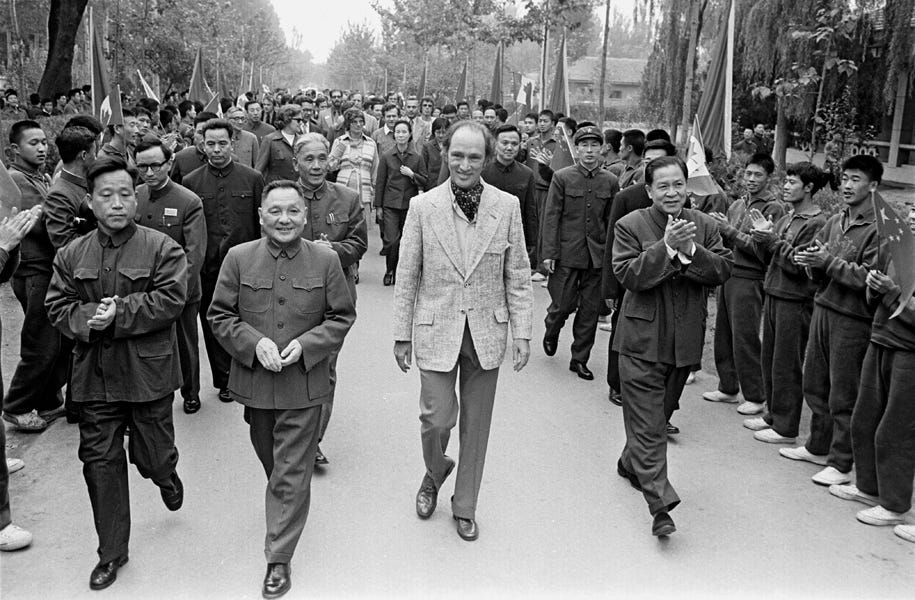

At that time, the Canadian government had no link with China. That didn’t happen until five years later when we established diplomatic relations. Negotiations for recognition were initiated by Pierre Trudeau, the father of Justin. He had visited China twice – one of the few Canadians who actually had been there – and he wanted to open up China to bring it out into the world. He said, “You can’t keep such a huge country of 700 million people isolated from the rest of the world.”

Public opinion had changed. Until the mid-60’s Canadians opposed establishing links with communist China. But by 1968, a majority of Canadians favoured establishing relations. We had began to sell China wheat in the early ‘60s – huge amounts of wheat; hundreds of millions of dollars – because they needed the food. They were really hungry. After the Great Leap Forward, China really was struggling.

So, the idea was, “Yes, let’s do something with China. If we can sell them all that wheat, why not have diplomatic relations?” It took two years. We negotiated, we established relations, and in the process gave up our diplomatic links with Taiwan.

You could say that in the ‘70s we were trying to build a new relationship with China. We thought this was a big achievement. Hey, we beat the Americans to the recognition of China. They actually didn’t recognize China until ’79. In that first period, we began to figure out what trade potential there was, and nobody talked about human rights. That wasn’t on the table at that point.

We began to trade more actively, established a large development assistance program, and encouraged people to people links. Began to send our students there, and the Chinese allowed some of their people to reunite with their families in Canada In the 80’s, Deng Xiaoping said it was time for China to go out into the world, “to jump into the sea.” Beijing said it was a “golden decade of relations.”

Maple Kingdom: Culminating in the Southern Tour and that era?

B. Michael Frolic: Oh, yes.

The southern tour was later, in the 90’s, and very important. Deng said, “We have to engage with capitalist markets,” unlike the Soviet Union, which never could do it, and that economy struggled. I continued to spend time in the Soviet Union in the 80’s because I was doing research there. You could see the difference. And then at the beginning of the 90’s the Soviet Union collapsed in a puff of smoke, so to speak.

After 1970, we established development assistance programs with China. Our trade expanded, and we talked about close friendship ---some even thought China would open up politically. China was talking about not just one communist party, but maybe several parties, and it looked like it was slowly liberalizing.

Then came Tiananmen in 1989 and that was the end of this first period. The second period begins with China’s troops killing its citizens. We saw this on TV. The tanks killing unarmed citizens just turned everything around. And many people were suddenly saying, “Hey, China is not good at all. China is doing very bad things.” We strongly criticized China.

China refused to acknowledge the criticism. We applied sanctions on China, but in the book I say that these sanctions never really had an impact. Sanctions are rarely successful. Maybe South Africa – enough countries sanctioned it for enough years so that finally apartheid collapsed, but I’m not so sure it was just because of sanctions.

So, we tried for four years to sanction China. It didn’t work. We employed many strategies to criticize China’s human rights practices. They failed to have an impact. We started to trade much more actively with China in the mid 90’s and focused less on human rights.

Tiananmen had changed the landscape. In the ‘90s, we were trying to figure out how to deal with an authoritarian China that wasn’t liberalizing. We could never go back to the so-called “Golden Age” of the 80’s. Then came the 2000’s, Harper came into power in 2005 and said, “We’re going to treat China as an adversary. China’s not a good partner for Canada. Its human rights record is particularly bad, and they engage in a lot of espionage”.

In 2010, however, pressure from the business community forced Harper to improve relations. “Look, we have to have better links with China. Canada can’t just keep bad-mouthing China. We have to preserve the high-level contacts that we have to promote trade. We need good relations to maintain those connections.”

After 2000, China began to change. It became more aggressive and less interested in being an equal partner with Canada. It was becoming a superpower and increasingly viewed us as a subordinate partner. China was going to not going to pay as much attention to us anymore, and when it did, it would demand a lot more, in trade concessions and in other areas. There was talk of a free trade agreement, but the two sides could never agree.

Justin Trudeau was elected in 2005 and tried to finalize that free trade agreement, but it didn’t work out. Then, Trump initiated trade sanctions against China, impacting Canada’s links with the PRC.We were caught in the middle between China and the United States. The United States suddenly was no longer the best friend and supporter of Canada that we thought it was. Trump and the Americans imposed tariffs on us and interfered with our China trade.

Then, the Americans asked Canada to detain Meng Wanzhou in Vancouver for extradition to the U.S. to be prosecuted. We had to honor a request like that. Once that happened, the Chinese immediately arrested the two Canadian Michaels. Michael Kovrig was imprisoned for 1000 days. Every day he walked 1,000 steps in his cell-like room. The Americans eventually made a deal to return Meng Wanzhou to China, and the two Michaels were released back to Canada.

By then relations with China were at their lowest point since recognition. How to reset relations? Our government said it was putting together a new China strategy. I don’t know what it is. I’m not privy to that, nor are many of us in the China policy community. Some people say we do have a document that’s ready to go. Other people ask, “Well, what would be in that document?” My book offers some suggestions.

Currently we also have appointed a high level group to develop a new strategy for the Indo-Pacific region—to diversify our trade, and to serve as a counterweight to China. This will have a significant impact on how we rest relations with China.

To recap, period one goes from recognition to 1989. In those 20 years we built a promising relationship. During the second period– post-Tiananmen to Harper in 2005 – we tried to figure out how to deal with an authoritarian China that was not liberalizing, was not going to act like Western political systems, and working with China in multilateral institutions was no longer that helpful. Trade became the big thing. “Well, let’s trade with them, promote education, and encourage people to people links.”

Then you have the last period. It begins with Harper, through to Justin Trudeau, and relations broke down as we tried to come to terms with a new, less friendly China. Some have called this the era of Chinese wolf warrior diplomacy. Chinese superpower aggressiveness transformed bilateral relations, highlighted by the two Michaels situation.

We’re struggling with that. Today China is a superpower, but we should remember that when we first started relations in the 70’s, China was very poor, lacked infrastructure, and we gave them all kinds of help.

In the early period, size and geopolitical significance were not so important. We considered Sino-Canadian relations to be one of equals – even when they were much bigger and had many more people, but now it’s become quite different. We’re dealing with a large superpower, like the Americans – another superpower, and we are, as China says openly, “a small, weak country.”

How to adjust our thinking and maintain our self-respect as a nation and our sovereignty, to meet the challenge of today’s China? We are not a force that can change China. We never were.

Some Westerners have thought, “Oh, we can change China.” The lesson of such attempts over several hundred years was – that you can’t. Whether it’s Jesuits, or imperialists, or people who love socialism, you can’t change China to be like us-- if China doesn’t want to change. That’s a lesson that we had to learn, and today we have to think: what is it in the relationship that is important for Canadians?

In my opinion, what’s important is the following: Two million ethnic Chinese-Canadians having links with China. Two way trade worth $100 billion. Close to two hundred thousand Chinese international students coming annually to Canada, bringing as much as a billion dollars to help save our educational system. Working together on global issues, such as disarmament, anti-terrorism, and global warming.

Human rights? Well, that’s one of our big concerns. We’ve just not been able to have any traction with China on human rights-- nor has any other country. A chapter in the book addresses this issue.

So, that’s basically my overview.

Maple Kingdom: One of the parts of the book that I found compelling was your discussion of Team Canada and the Chrétien era. Can you talk a little bit about what made that moment special and how you place it in the narrative of the bilateral relationship?

B. Michael Frolic: Well, remember that the Team Canada visit occurred in 1994. That’s five years after Tiananmen.

Maple Kingdom: It’s incredible.

B. Michael Frolic: Yes. By then, almost every other country, including Europe, America, had already abandoned their criticism of China. We were among the last to give up our sanctions. Some people argue that the Team Canada visit marked the official end of our sanctions.

I think it may have happened a little earlier. Chrétien, who came to power in 1993, said, “We’ve got to do something with China now that things are changing. I want to focus on trade.”

I was fortunate to have the Canada-China Business Council help me with that chapter, in particular, former senator Jack Austin. People in Foreign Affairs also provided a lot of information. The visit was quite extraordinary. Canada never had an event like that, where a prime minister was able to include every provincial premier-- except Québec-- on a trade mission. Despite their egos and their provincial agendas, they all managed to get along with each other when in China. I was watching the visit from Canada--- I wasn’t in China that year, although I went there again soon after. Everybody was enthusiastic, including the Chinese. The Chinese officials with whom I spoke said that the trade mission had restored relations.

Team Canada cost a fortune to organize, and that’s why they only had two or three more. Ottawa finally said, “It’s just too expensive to run these huge trade missions.” After 2001, the Canadian business community didn’t need top level access in China anymore because opportunities had opened up. They didn’t need a prime ministerial visit to promote trade.

I’m glad you liked that chapter. I liked it, too.

Maple Kingdom: I want to delve a little bit into some of the changes between this new work that you’ve just come out with and some of your previous works. I wanted to talk about how you prepared this more grand and overarching narrative. Can you share a little bit about your favorite interviews in the research phase of this book and who you believe really contributed to your understanding of the bilateral relationship?

B. Michael Frolic: We’ve should look at my first book, “Mao’s People,” which was about the Cultural Revolution. It was my introduction into the study of China. I started it when I was in Hong Kong in 1972. That was where I could interview people, because you couldn’t do any research in China. My respondents had escaped during the Cultural Revolution. (Editors note: out of mainland China to HK which was at that time under British control.)

I returned to Canada and put the whole thing together. It established me as a China scholar, and I wrote several books afterwards. Paul Evans- then at York and now at UBC- and I edited a book on Canada and China from ’49 to ’70. In the 80’s and 90’s, Evans and I pioneered the study of Canada-China relations.

In the 90’s, I looked at possible liberalization of China through the growth of civil society there. I had spent time in China in Canadian-funded civil society projects. Had developed a theoretical approach called “state-led civil society,” and edited a book on Chinese civil society with Tim Brook- then at U of T, and now at UBC. I was teaching Chinese politics at York, going to China almost every year, and working in Canadian government programs in China-- whether it was the Ontario-Jiangsu Exchange Program where I would bring students and faculty back and forth, or CIDA projects. I also was working on Sino-Soviet relations, and alternated going to Moscow and Beijing, to talk with academics and senior officials. .

That was in the ‘90s. China was definitely not going to open its archives to any foreigner. So, I wanted to talk with the Russian experts who had come to China in the ‘50s to help China. They even had an association of Russians who had worked and in China, and then returned to the Soviet Union, but they were not ready to allow a foreigner – you know, a non-Russian, and non-communist – to work with them, so I gave that project up.

I spent the 90’s into the 2000’s writing a bunch of articles and reports, on trade, human rights, Tiananmen. You know, a little bit here, a little bit there.

Then I said, “You know, maybe I should be thinking more broadly about the whole Canadian link with China.” I’m one of the few who have been in China before we had relations and I’m still alive now. Maybe I can offer some perspective, or at least continuity from the past to the present. A book about our relations with China since 1970.

It took a lot longer to write this book, much longer than I ever expected. Ten years at least before I finally had a working draft. Part of that was because of two things. When Harper came to power, he shut down access to the government files for academics. I couldn’t get files or talk with our officials. So, everything shut down under Harper. I said, “I better wait a bit until things loosen up again.”

That was a setback. By 2012, I realized I could finish it off. My wife was complaining, “Finish this book off. You’ve got notes all over the place.” So, in the next few years, I was able to do that, until the Chinese hostage taking and the banning of some of our exports. That was the second obstacle, and it resulted in another three year delay.

I had excellent access to decision makers – over 100, and 40 or 50 ministers, prime ministers, and senior officials. I was also close to Chinese officials because they saw me early on as somebody who had been briefly plugged into government. I was often consulted by both sides.

Finally I could see that I had enough material and I also had my personal diary. I keep a diary of my travels and my political encounters and have 1,000 pages of diary notes, from living in, and visiting both Russia and China. I quote extensively from this diary in the book.

So, that’s how the book was put together. People were constantly pestering me and saying, “When is this thing going to be finished? You’ve got to write it. Why isn’t it done?”

I couldn’t cover everything. I had to go where the material was available, and where the stories were interesting, where it meant something for Canada’s relations with China. So, there are things missing. I don’t talk much about Hong Kong, or about ethnic issues and the problems in Tibet and Xinjiang, although they are part of my human rights chapter.

I don’t talk much about the environment, which I find is only developing recently as an important part of the relationship. So, there are things missing. I certainly couldn't interview all the prime ministers. I managed to interview five.

Three times, at least, I was able to talk together with Trudeau (editor’s note: Pierre, not Justin). He gave me a sense of how and why we began relations, and what the strategy was--that it wasn’t designed to make China democratic; it was designed to open up China to the outside world, and that was number one.

The most important people for me when writing the book were not the ministers, whom I could talk to, and from whom I got a lot of material; and not even the prime ministers, but our 15 ambassadors. They could tell me what was going on in the field, what they were doing when we made a decision in Ottawa about development assistance, or human rights, or trade.

They were willing to talk about these things to me. It meant a lot to them. They were one of the main sources for the book.

Maple Kingdom: Wonderful.

B. Michael Frolic: There were a few other people in Foreign Affairs who went out of their way quietly to help. Remember, most government officials do not want to be identified. Many of them choose to remain anonymous when talking about government policy--secrecy is a very important part of diplomacy.

So, we have to navigate within that limitation, and that’s not always easy.

Maple Kingdom: Another piece of the book I found really compelling is your capacity to explain our “Third Country” status. If you were giving advice today to young people who are interested in understanding Canada & China diplomatically, would you study the United States?

B. Michael Frolic: I always felt that the United States was looking over our shoulder. We acted, or thought we were acting, independently with China. But that was not the case.

We were always influenced by what the Americans were doing. In the early period, when we recognized China nine years before the Americans, we thought, “Hey, this is great. We’re way ahead of them with our China policy.” That fit in with Trudeau’s foreign policy at the time, which was to lessen our dependence on America in foreign affairs.

When the Americans fully recognized China in 1979, we weren’t that special anymore to China. Back in 1970, Chairman Mao had said, referring to Canada, “We now have a friend in America’s backyard.” America was always China’s prize, not Canada. For a long time China used Canada as a “stepping stone” for determining its relations with America.

Whatever relationship China has had with us, its first concern was always U.S. China policy.

We understood that we were within the American orbit, although we often pretended that we had an independent China policy.

In 2017 the Chinese said we were a “running dog” of the Americans, (editor's note: Chinese culture historically does not view canines as man’s best friend, but instead a lowly creature. 走狗 is a big-deal insult) a lapdog. Are we the lapdog of the Americans? No. I don’t think so. But our values resonate with the Americans, and we mostly agree with their China policies.

Things unraveled during the Trump period. We were caught in the middle between the Chinese and the Americans. The two of them control the China narrative. It’s superpower to superpower and we’re tacked onto the Americans. We can’t anymore play that game where we pretend we are independent of the Americans. Post-Trump things have improved, but our China policy, for better or for worse now goes through Washington—the Americans brokered the deal that freed the Canadian hostages.

That’s always in the back of everybody’s mind – the link or non-link with America. What are the Americans doing? Oh, well, they’re doing this. Should we do it differently? They have the money, they have the resources, and the military capacity. China will listen to them first. But at one point in time, China used to listen to Canada because they saw us as a stepping stone – as a way to get at what American policy was.

I don’t think that’s the same anymore. Canadian China policy now goes through Washington.

Maple Kingdom: Thank you. One of the things that I think is really compelling about your experience is the fact that you can see both the good and the bad of the relationship over this 40- or 50-year journey. Can you speak a little bit about the way that Canadians see China, and the differences between the perception of China inside of Canada and the reality of China on the ground as you experienced it?

B. Michael Frolic: Well, you have to say, “Which Canadians? And what do they really see? How much information do they really have? Can you trust public opinion polls – today’s polls vs. the polls three months from now?” You have to look at all these things. You can say, “Well, right now, less than 20 percent of the people in Canada think we should be that friendly to China.”

The current polls show we have the worst relationship ever with China. People don’t trust China. All those cheap goods that have affected our manufacturing sector. They continue to steal our secrets and our IPR. They have these big state-owned enterprises that are dominating our trade.

The Chinese community in Canada is a prime PRC target. China tries to get into their local newspapers, to influence their media, and to promote “the Motherland.” This is a direct assault on Canadian sovereignty and a real concern for Canadians. Then, of course, there were the two Michaels. The image of Meng Wanzhou, always beautifully dressed, having two houses in Vancouver, seen on TV looking smart, attending university, and going about her life, sharply contrasted to the two Michaels confined in tiny windowless rooms.

This made Canadians angry. Also the problem with the Uyghurs, always Tibet, and what happened in Hong Kong, the whole human rights situation, and China’s aggressive wolf warrior diplomacy. Wang Yi, the foreign minister, came to Canada and in a press conference openly showed a lack of respect to our Canadian Foreign Minister, Stephane Dion.

A reporter asked Stephane Dion about human rights in China, and Wang Yi jumped all over him saying, “You have no right to talk about that”.

Then, of course, you had Lu Shaye, the Chinese ambassador who was the previous ambassador, who spent his time in Canada constantly criticizing everything we did in a quite nasty way Finally he left, and went to France where he is doing the same thing. That is called wolf warrior diplomacy.

Trump, Trumpism, and blaming China for COVID… You know, when all this is going on, particularly on our West Coast and in our Chinese communities, it’s not the best time to have a favourable opinion of China today.

As far as the Canadian government is concerned, I can’t speak for Ottawa; but it is concerned about China’s aggressive diplomacy towards Canada, and what China is doing in multilateral organizations.

David Mulroney, a previous Canadian ambassador to China wrote in his book – “You don’t have to like China or love China to have a relationship with them.” That’s where I go. No matter how difficult, keep the links open—but be wary. I say, “Look, I lived in the Soviet Union during the Cold War in the ‘60s for a year. It was a terrible place. Everybody was spying on me and it was difficult to get around.”

“You couldn’t read Western newspapers, you got all this propaganda day-after-day, but we kept our links with Russia. We had diplomatic relations. I could travel from west to east and do my research. In our Western rules-based world you can have relations with a state that is not following acceptable diplomatic or nation-state behaviour.

China is the second superpower in the world. We have $100 billion trade with them. We’ve got all these things going on in education, and we have our 2 million ethnic Chinese Canadians. How can we simply shut down? No, we can’t. So, we have to find the areas where we can maintain links, and wait and see if China’s behaviour changes.

The Party Congress in a week. Once that’s over, there may be a different political landscape in China. The American elections are coming up also. Sino-American relations might change, depending upon who wins in the November mid-terms. There are things going on now that can possibly calm tensions.

There may be gestures that each side can make in order to open up relations and improve them, but many of our government links with China are basically frozen. We had 40 different dialogues with China that we’ve set up over the years. Hardly any of them are working. There’s just nothing going on.

Maple Kingdom: I want to ask you a little bit about your media diet and how you keep up-to-speed on the relationship between Canada and China.

Books! There’s a ton of books. When I first got into the China field in the late ‘60s, one or maybe 4-5 books a year about modern China were published. Even my book in 1980. There weren’t that many other books. Now, hundreds of books on China are coming out every year.

You cannot keep up. And today’s books are so specialized. There’s even a new book on Chinese grandmothers. Who ever wrote about Chinese grandmothers? Well, she’s a good friend of mine. Diana Lary, a professor at UBC. China scholars are so super-specialized that you can’t keep up.

Until three years ago, I went to China every year. 61 times I’ve been to China. I went every year because I’ve run this this York University training program for over 20 years for Chinese officials, businesspeople, entrepreneurs, and educators.

Maple Kingdom: Thanks for your time today. Closing thoughts on the China-Canada relationship today?

B. Michael Frolic: Right now Canadians aren’t that concerned about China. There are so many other things catching their attention, so it’s hard to get people focused on China. The recent appointment of our new ambassador wasn’t enough. We need something else to get people focused on Canada-China relations again. Maybe after the 20th Party Congress.

The Congress will crown Xi Jinping emperor. Now China has to deal with its economy. It may become less aggressive in international affairs. Much will depend on U.S. China relations. I don’t think China is ready to do “a Ukraine” with Taiwan. As for resetting Canada-PRC relations, that may still take time to resolve.

Maple Kingdom: B Michael Frolic, Thank you again.

B. Michael Frolic: This has been great, all the best.

Maple Kingdom: All the best. Bye now.